BizChina

- Details

- Hits: 1022

One of the things we lawyers have to live with is secrecy. Put simply, if we reveal client confidences we can lose our licenses. This necessarily leads us to be über careful.

I have been uber careful about not mentioning a transaction in which my firm represented the Chinese company VanceInfo. The transaction was between VanceInfo and Expedia and I was not comfortable writing anything on it until I was 100% certain it had gone public. Working with VanceInfo's in-house legal team, my law firm provided the US side legal representation in negotiating the contract with Expedia and related activities.

But even now, I am constrained from revealing anything substantive beyond that which has already been made public. I have to be particularly careful because VanceInfo is a publicly traded (NYSE) company. But I wish to highlight this deal because I see it as a harbinger of the sort of thing we will all be seeing more of from Chinese companies as they expand worldwide.

So I waited and waited and never saw anything.... Until now.

I saw that VanceInfo started following me on Twitter and so I checked out its Twitter page and learned it consists (so far) of one Tweet, and that one Tweet links over to their September 23, 2009 press release announcing its deal with Expedia on which my firm and I worked so hard.

The press release states the following:

Beijing, September 23, 2009 -- VanceInfo Technologies Inc. (NYSE: VIT) (“VanceInfo”) (the "Company”), an IT service provider and one of the leading offshore software development companies in China, today announced the official launch of an offshore development center (“ODC”) in Shenzhen, China with Expedia, Inc. (“Expedia®”), the world's leading online travel company. The opening ceremony will be attended by Chris Chen, Chairman and Chief Executive Officer of VanceInfo and Pierre Samec, Chief Technology Officer and Global Executive Vice President of Expedia®. After the successful completion of a four-month preparatory and transitional period, VanceInfo established the ODC in accordance with the multi-year contract with Expedia signed in May 2009. The two companies have worked together to build a global delivery team in the ODC that provides design, development, testing, production, and maintenance of online travel services platforms, enabling Expedia to enhance the core platforms and services while improving time-to-market and increasing competitive agility."We are pleased to be selected by Expedia following a stringent vendor selection process that involved many outsourcing players in China,” said Chris Chen, the VanceInfo CEO. “Our collaboration with Expedia has reached a new milestone with the seamless and successful completion of multiple project transitions while launching the new ODC. Leveraging China’s unique talent advantages, we are committed to delivering first-class IT services with flexible delivery models to support Expedia’s global expansion.”

VanceInfo has built and currently operates ODCs for multinational corporations in technology, telecom, financial services and manufacturing industries. This new Shenzhen-based ODC marks a breakthrough for VanceInfo in the travel and transportation industry and is anticipated to further enhance the Company’s overall global delivery capabilities to service major outsourcing initiatives of multinational clients.

VanceInfo was formed in 1995 and it already has more than 7000 employees worldwide and three offices in the United States, including one in Seattle, which is also where Expedia is based.

We are honored to have represented VanceInfo on this important deal and to have had the opportunity to work with so many great people on its management team.

Read more: China's VanceInfo "Done Good" And We Are Honored To Have Helped.

- Details

- Hits: 1536

Advertising Age Magazine just came out with its list of "20 Blogs Marketers to China Should Be Reading " and I like it. I like it not just because it lists China Law Blog (though I will admit I have trouble seeing past that), but because it provides a diverse list of blogs, every one of which I consider to be good.

I like how it includes well deserved classics like Danwei and Peking Duck, deep think blogs like China Beat and James Fallows, top newcomer blogs like Aimee Barnes and China Smack, not boring legal blogs, China Hearsay and IP Dragon, and cutting edge China marketing blogs like China IWOM and China Youthology.

I also like how its list is alphabetical, which calmed me a bit after I realized that was the case and it was not ranking us at #10.

If you are interested in China (and that is why you are here, right?) I urge you to check it out.

What blogs are missing?

Read more: Ad Age's 20 China Blogs For Marketers. Oh, And Everyone Else Too.

- Details

- By Steve Dickinson

- Hits: 1289

We are writing about joint ventures so often these days because we are seeing a pronounced resurgence both in companies wanting to go into Chinese joint ventures and in companies coming to us needing legal assistance with their failed and failing joint ventures here in China. We have often expressed cautions about joint ventures in the past, and nothing we have seen recently causes us to change our mind.

In many cases we are not able to effectively assist the foreign party in a troubled JV because their original joint venture agreement has been so poorly drafted as to preclude any real assistance. We usually attribute this to the foreign company's originally misinformed view that "China has no law" or that the "JV contract is not worth the paper it is written on." Based on this view misguided view of Chinese law, the foreign joint venture participant failed to secure good legal representation when it went into the joint venture deal, leaving us with little or nothing to work with in terms of fixing the joint venture problems. The foreign joint venture participant has made basic mistakes that make it impossible to use the very effective Chinese laws and legal system to resolve the problems that have arisen in the JV.

Some examples of the basic mistakes are:

-- In order to resolve a joint venture dispute, it is an absolute requirement that the issue be resolved in China, either through litigation in the Chinese courts or through arbitration with CIETAC, BAC (Beijing Arbitration Commission), or some other legitimate Chinese arbitration body. Foreign partners often provide in the JV agreement, however, that litigation or arbitration must take place outside of China, either in the home country of the foreign partner or in some expensive and well known arbitration forum like Stockholm or London. This type of provision does little to nothing to protect the foreign partner and makes it impossible to resolve any disputes in China, where the problem exists.

To take an example, many clients come to us complaining that the JV's representative director has highjacked the operations of the China joint venture company and is operating without supervision and against the wishes of the board of directors. To effectively address this issue, it is imperative that we proceed in court in China directly against the rogue director. However, if the JV Agreement provides for jurisdiction outside of China, we are effectively precluded from taking such direct action.

This is only one way that foreign participants in JVs sabotage their own chances at resolving disputes. Other examples are:

-- Failing to hire their own independent legal and accounting advisor during the formation process, thereby relying on the Chinese JV partner for all of the formation legal work. This is a guaranteed disaster, and it still happens every day. We have seen US companies that have put tens of millions of dollars into a Chinese joint venture, using no legal counsel at all, using the legal counsel of their joint venture partner, or using a local Chinese lawyer who has no experience with foreign joint ventures and no real incentive to protect their foreign client. We had one client who when he first came to us boasted of the great job his Chinese lawyer had done for only $600. When we pointed out how his joint venture so heavily favored the other side that his multi-million investment would likely never yield him a penny, we began to suspect he no longer thought of his counsel as such a bargain.

-- Relying on a majority share interest to control the venture, rather than exercising effective control through the right to appoint the representative director and the general manager.

-- Relying on a personal guarantee from the Chinese JV partner as a substitute for failing to properly document the project.

-- Failing to provide clearly for protections for the foreign partner, assuming share ownership is sufficient to provide adequate protection.

-- Failing to carefully monitor capital contributions and the use of contributions to capital, assuming that accounting reports will be adequate to reveal the fate of money contributed.

Though the above looks like a long list, I often see joint ventures where the foreign participant has made every single one of these mistakes and more that I have not mentioned. When this happens, we as lawyers are severely constrained in terms of what we can do to help. But this is not because China has no law or because Chinese contracts are worth nothing. It is because the failure to properly form and manage the JV has made it impossible to proceed. This blame for this generally falls on the shoulders of the foreign JV partner, not on the Chinese side or the Chinese system.

Joint venture agreements are really no different from any other contract. The better the agreement, the less likely there will be problems and the more likely there will be a quick and inexpensive resolution to whatever problems arise.

Read more: China Joint Ventures Again. This Time We Blame The Victims.

- Details

- By Jim Jubak

- Hits: 995

In a train wreck, there comes the moment when it's no longer possible to avert disaster. Pull the brakes as hard as you can, the momentum of the train is so great that disaster is unavoidable.

I fear that China's economy passed that point of no return in the second quarter of 2006.

Today, I'm going to tell you why I think China's economy is headed for a train wreck. Not tomorrow, but in the reasonably near future. I'd say 2009.

And in my next column, I'll sketch out the likely effects of that train wreck on the rest of the global economy and the folks, like you and me, who invest in it.

If you've been following the debate in the U.S. about the likelihood that cheap money here has produced a bubble in housing prices, you're already familiar with the basic scenario for a train wreck in China. Cheap money makes it easy to borrow to buy assets. That produces an asset bubble -- in the United States, first in stocks and then in real estate. As the asset bubble grows, borrowers get in over their heads as their judgment is overwhelmed by the excitement of rising prices. And lenders under the influence of similar emotions make loans to unqualified borrowers.

Read more: China's steel industry lead its economy out of control

- Details

- By David Cao

- Hits: 1169

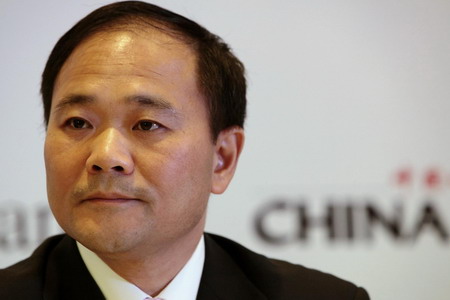

Li Shufu, the founder of China's Zhejiang Geely Holdings, has much in common with Henry Ford, from a childhood on the farm to a scrappy determination to build a car-making behemoth from nothing.

If discussions underway between Geely and Ford Motor Co are successful, he may have another link with the great industrialist -- ownership of Ford's Volvo unit.

Li's Geely, which means auspicious or lucky in Chinese, has captured the imagination of car buffs worldwide with its dark-horse bid for the well-known but money-losing Swedish brand being sold by Ford.

More Articles …

Page 96 of 120