Job applicants flip through newspapers searching for employment information at a job fair held at the National Agriculture Exhibition Hall in Beijing late last month.

As nation battles to reduce unemployment, analysts say it is shortage of skilled workers, not jobs, that is causing problems. Daniel Chinoy and Wang Xiaotian report from Beijing.

Song Yongliang did everything right. He worked hard, went to college and majored in Russian, which he thought would be practical in his hometown in Northeast China.

In his senior year, he found an internship as a translator and hoped to find a job with a trading company near the Russian border after he graduated in 2008. Then the financial crisis hit.

Trading companies cut back on hiring and, for a graduate with minimal experience, Song's prospects looked grim, forcing him to take whatever jobs he could find. He worked as a translator in Beidaihe, a seaside town in Hebei province, and on Hainan Island, and even spent a brief, unhappy period at a relative's alcohol factory in Shandong province.

Frustrated but unbowed, the 28-year-old eventually made his way to Beijing, where he found work as a salesman and then a recruiter for a private school. The pay was meager, the hours were long, and as time went on, it became more difficult to hide his disappointment.

"I went to college, spent all that money, and yet you can make more money working as a security guard or a waiter here," he said.

"I definitely thought about it. My parents would have lived more comfortably and I would have lived easier. But it would have been a huge loss of face, an admission of failure. Did I spend all that time in school preparing to become a security guard? I studied hard for four years and my parents supported me. Do I want to waste that?"

Song's experience highlights what experts say is an increasingly large gap between the kinds of jobs that are available in China and the skills and interests of workers able to fill them.

Although particularly acute for college graduates, the situation extends across the Chinese economy, all the way down to the country's millions of migrant workers. Indeed, some economists argue that the new challenge for Beijing

is not a lack of jobs - Song, after all, found at least six - but a lack of jobs that fit the people looking for them.

A recent survey by the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security found that demand for workers was up 15 percent compared to last year. A serious labor shortage has been reported in the Pearl River Delta, where factories may need at least 2 million more workers to meet demand. According to human resources consultants Towards Watson, salaries have risen rapidly in China in recent of years, and will grow by about 10 percent this year.

Yet unemployment remains high. The government's official figure of 4.2 percent only counts those who register as unemployed, excluding migrant workers and those who choose not to tell the government. A survey by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) estimated that real unemployment in China was actually closer to 9.4 percent in 2008. (A recent report to the State Council proposed an official national survey that is released to the public. Analysts say it could be approved soon.)

In addition, for the past decade, the number of people of working age has increased about 10 million annually, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. That is the equivalent of adding more than the entire population of New York City to the Chinese economy every year.

"There is a pretty clear contradiction in the labor market," said Zhang Juwei, a professor and director of the labor and social security research center at the CASS. "Many businesses can't find workers but, at the same time, many people can't find jobs either."

As this trend has become clearer, the central government has recognized that it is a serious problem, and vowed to find a solution.

In an online chat with netizens on Saturday, Premier Wen Jiabao said: "Every year 150 million migrant workers leave their rural homes to seek jobs in cities, 24 million urban unemployed are waiting for jobs, and the number of university graduates will hit a record high of 6.3 million this year, all adding to the employment pressure."

It is a "very important task" for China to create job opportunities, said Wen, who encouraged graduates to start their own businesses and voiced the hope that the employment situation will be better in 2010.

Employment is likely to be a major topic for discussion at the annual session of the National People's Congress (NPC), the country's legislature, which begins today.

"It will definitely be a hot topic," said Lian Si, a professor at the University of International Business and Economics (UIBE) who authored a book on urban communities of struggling graduates called Ant Tribe. "The government is paying a lot of attention to this problem."

"The employment question looms over virtually all political discussion in China, whether it comes up explicitly or not," said John Delury, associate director of the Center on US-China Relations at the New York-based Asia Society.

The mismatch between workers' abilities and the skills that many jobs now require is partly the result of China's natural development, said Pan Chenguang, a human resources expert at CASS and the author of the 2009 Report on the Development of Chinese Talent.

"China's economy is not the same agricultural economy it used to be," he said. "As the economy has shifted towards production there is less demand for ordinary, unskilled labor. As a result, there is an excess of unskilled workers and an enormous lack of skilled workers."

Song Baohua (no relation to Song Yongliang) was laid off from his job as a supermarket cashier in Beijing in November. "It is still difficult for us to find a job, especially for an older person like me," said the 55-year-old from Wuqiao, in Hebei province. "Employers want people with technical skills."

This has still not translated into easy jobs for the college educated, however, in part because, as Song Yongliang discovered, an educated worker is not necessarily a skilled one. "Most companies want someone with experience. There are lots of jobs that college graduates want to do that they can't and many don't want to do certain jobs," he said.

"Our universities encourage research and theory, and there are relatively few vocational schools," said Pan. "Moreover, most students feel that the social status of attending a vocational school is lower, so they don't want to go. But what society needs is people with skills."

New workers at Huachen Brilliance Auto Factory in Shenyang, Liaoning province, for instance, need experience in welding, distribution or logistics, car maintenance, or electronics - knowledge that Song Baohua, Song Yongliang, and most college graduates and migrant workers do not have.

"As a result of an influx of new technology and management ideas, the type of workers we recruit has changed completely," said Li Xuelian, a spokesperson for the factory. "The quality of people we recruit is much higher now."

The structure of the Chinese educational system also plays a role, said Lian at the UIBE. Chinese universities usually decide the number of places for each major and then recruit students to fill them based on their university entrance exam scores, rather than letting students choose majors.

"We have a market economy but majors are still chosen through a planned system," said Lian. "Maybe we don't need that many international relations majors but we still train them anyway."

This means many university graduates are either not qualified for or not interested in the jobs that are available to them, he said.

Another reason college graduates have struggled to find work is that there are simply too many of them - a legacy of the government's efforts in 1999 to simultaneously improve the quality of the workforce and fight unemployment by dramatically expanding the country's higher education system. That year, college enrollment was increased by about 47 percent to 1.6 million students. The result, however, was not quite what was intended: a huge increase in the number of graduates that the Chinese economy remains unable to absorb to this day.

In 2008, there were 5.59 million new graduates and about 1 million did not find jobs. Last year, 6.11 million students graduated, and according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, 87 percent found jobs. Analysts say that number is vastly inflated because of both dishonest reporting by colleges and the fact that, like Song, many graduates were forced to accept low paying jobs they did not want.

Hundreds of thousands of them now live in what have been dubbed "ant communities", decrepit, cheap and rapidly expanding towns outside major cities. Lian estimates there are about 1 million "ant" graduates, including about 100,000 in Beijing.

These unemployed and underemployed graduates and laid-off migrant workers could be a catalyst for instability - a fact that partially explains the government's attention to the issue, analysts say.

"If people lose their jobs, of course it impacts social stability," said CASS professor Zhang. "I don't know of any country where that's not true. It involves people's livelihoods and jobs. This is something the government should think about before anything else."

Susan Shirk, a professor at the University of California in San Diego and director of the Institute for Global Conflict and Cooperation, agreed and said the high expectations and organizational abilities of unemployed recent graduates make them a potentially volatile group.

For now, most members of the "ant tribe" are still willing to work and to hope, said Lian. "The road upward is increasingly narrow and difficult. It's not a problem of social instability yet but it is a potential crisis."

"If the distance between someone's dream and reality is too great, their spirit simply won't be able to take it. Especially in poor people's families, where they always hear that knowledge can change their future," said Song. "But if the jobs they dreamed of and the pressures of reality meet and their dreams die, what options do they have?"

Migrant workers, too, have not yet become a source of major social instability. Despite the financial crisis - which the National Statistics Bureau said caused Chinese exports to drop 16 percent and, according to the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, cost an estimated 20 million migrant workers their jobs - it is striking just how few labor-related protests there have been over the last year, said Shirk.

One reason, she argued, is that the 4-trillion-yuan ($586 billion) stimulus package launched by the State Council in November 2008 was largely successful. "The stimulus was very effective. It came in early, just when it was needed, so it had the right kind of Keynesian boost to demand," she said.

Another possibility is that many of the laid-off workers were migrants from the countryside and were able to return homes to their farms. "That creates a cushion because when factories slow down these folks can still go back to the countryside," said Shirk. "Their expectations maybe are lower. They don't expect that they have permanent employment," unlike the workers laid off by State-owned companies in the 1990s.

Still, social stability and employment are unlikely to recede as major issues, especially as both the demand for skilled workers and the oversupply of college graduates are likely to intensify in the next few years. But as the National People's Congress meets over these coming days, scholars say there are a number of steps the government can take.

One is to encourage enough lending to support the economic growth necessary to preserve job growth. However, as Shirk noted, if it goes too far, Beijing risks inflation, which could also undermine social stability. "Inflation really hits the middle class, the urban middle class. I think they worry about discontent from that group as well," she said.

Another option is to give migrant workers and college graduates more practical training. "China needs to strengthen its technical training, including for migrant workers, and make a college education more applicable," said human resources expert Pan. Lian at the UIBE also suggested the government focus on developing second and third tier cities to expand opportunities for graduates.

In the meantime, Song Yongliang remains frustrated he is unable to utilize the language skills he learned in university. But he still makes what he considers a livable salary - 3,000 yuan a month - and recognizes that in the current climate, it could be a lot worse.

"If this company still thinks I'm someone they can use, and I can learn a little bit while I'm here, I'll stay as long as I can," Song said. "This company has given me a job and a place to develop myself a little bit. I'm very grateful."

|

Small factory owners hold handmade posters to attract job seekers at a job market in Yiwu, Zhejiang province. The area is suffering from a labor shortage. Xu Kangping/for China Daily |

|

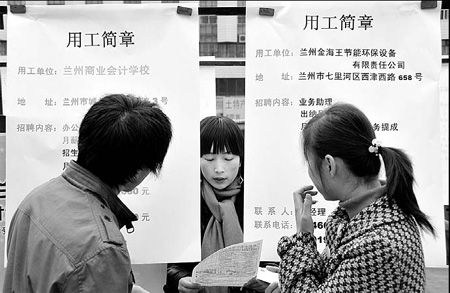

People scan the wanted ads at a recruitment fair at the Lanzhou Railway Station in Gansu province this month. Chen Mingzhe/for China Daily |