When he made the highest bids for food stalls at two local temple fairs that occurred during Spring Festival, Kebab King Gu Shengli was confident he would make millions.

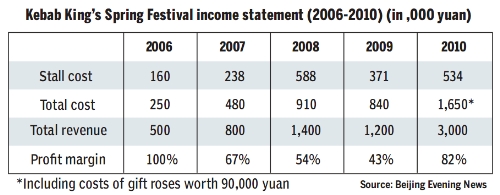

The two locations cost him a total of 534,000 yuan ($78,221). His colleagues estimated he would need to sell more than 150 yuan of meat every single minute the stall was open, just to cut a profit.

|

|

“Kebab King” Gu Shengli has his own way to survive the heated competition. [CHINA DAILY] |

However, the man simply shrugged off such concerns. Gu claimed he had made 10 yuan every second by selling Middle Eastern-style kebabs at previous temple fairs. He believed he could pull off the miracle again this year, despite the much higher stake.

And he almost did.

According to Beijing Evening News, Gu sold 150,000 kebabs at a price of 20 yuan apiece, and made a profit of 1.35 million yuan. However, Gu's new marketing campaign - a do-it-yourself barbecue kit - failed miserably, and wiped out almost all his gain.

The 100-yuan package included 10 uncooked kebabs and a small stove so visitors could cook their own or even have a barbecue at home. However, the packages were shunned by park goers and Gu is reportedly stuck with 1.27 million yuan's worth of unsold packages.

Despite the setback, Gu, 43, said he would continue to splurge on the prime-location stalls to ensure his "Kebab King" title in the future.

"The media reports have greatly helped with the branding of my products," he said.

Along with his barbecue staff, Gu has been expanding his kebab empire by attending nearly every big event nationwide, such as the International Beer Festival in Qingdao and the Agricultural Expo in Wuhan.

But Beijing's annual Spring Festival temple fairs remain primary events for him.

Besides being a risk-taker, the Inner Mongolian native is also known as a marketing maverick in the business. For example, this year at the Ditan Temple Fair, Gu encouraged customers not to queue by selling to those who cut the line.

"Those in the line would surge forward to form a crowd at the stall," Gu said. "And those who had struggled their way through would probably want to buy more kebabs."

However, next year, Gu will probably meet stronger business competition as the number of kebab stalls had increased at temple fairs over the years.

At the Ditan Temple Fair this year, 35 of the 40 stalls sold kebabs.

The Kebab King believes all his competitors need to spend more time improving the quality of their materials and roasting methods. Otherwise, "it will be difficult to break even."

Gu said he would continue to introduce marketing gimmicks similar to the unpopular barbecue kit, and has learned his lesson from the recent temple fair failure.