It is dance drawn from one of the most sensual books in Chinese history. The specially commissioned production for an arts festival was a sell-out success, but it may never be staged in the mainland. Chen Nan talks to Wang Yuanyuan, the choreographer of The Golden Lotus.

The creation and production of The Golden Lotus was an exhausting challenge for choreographer Wang Yuanyuan.

For Wang Yuanyuan, her stage adaptation of the 16th-century Chinese novel, Jin Ping Mei, or The Golden Lotus, was her most frustrating, exhausting, but also most satisfying, work.

That's saying a lot, considering her stable of works ranges from choreography for the 2008 Beijing Olympics opening ceremony to putting together China's most avant-garde dance productions, including Raise the Red Lantern and Haze.

The Golden Lotus, a Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) novel, has been considered one of China's naughtiest erotic works and has been banned for its explicit portrayal of sex, adultery and corruption in a decadent society.

The book devotes itself to narrating the sexual exploits of Ximen Qing and his many lovers, especially his three most famous mistresses - Pan Jinlian, Li Ping'er and Pang Chunmei - for whom the book takes its title. In her adaptation, Wang has focused on how the women feel, their fragility and delicacy. In a sense, she became their guardian angel.

For Wang, dance is the best way to capture the essence of the tale.

"Dance is abstract. It accurately captures sexual energy and leaves the audiences space for imagination," the award-winning former prima ballerina says.

The attention to detail that Wang goes into can be seen from a 5-minute video widely posted on the Internet.

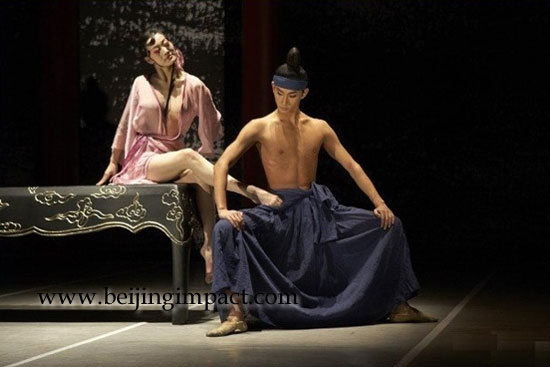

A traditional Chinese swing-bed rocks on a specially made beam. An ancient Chinese melody laced with electronic percussion sets the tone for passionate lovemaking between the corrupt Ximen and the equally infamous Pan Jinlian.

The dancers, in transparent gauze and nude bodysuits, unravel the tale of long-forbidden taboos under dim red lights.

Wang created the piece specially for the Hong Kong Arts Festival. It premiered in March this year and ran for four days. Wang and the dancers from the Beijing Contemporary Dance Theater won instant acclaim.

Tickets were sold out before the dance company even landed in Hong Kong. According to Wang, the praises were many and unexpected, and viewers described the performance as a "living oil painting".

When Wang brought the work back into the Chinese mainland in September, she encountered her first roadblock in Chengdu, her first stop. Eight months after the work's premiere, Wang has yet to succeed in staging it again, and she is resigned to the fact that its controversial content may have stopped its progress for good here.

"I don't think the work will be seen by audiences in the mainland soon," says Wang in her office at the Beijing Contemporary Dance Theater, a company she founded in 2008 after her successful adaptation of the kunqu opera, Peony Pavilion.

"It's like telling a child not to touch something dangerous. Kids are hugely curious. The more you tell him not to do something, the more eager he is to try," says Wang, who says she is in her late 30s, although her delicate features and taut body belie the facts.

"That's the case, too, with sex education in China. It's still a subject cloaked in mystery."

She had actually said as much when she expressed her doubts during the Hong Kong Arts Festival early this year. She had said then: "I don't know if this show can open in the mainland".

Wang understands that it is not a matter of the dancers being dressed or undressed that has roused the censors' attention. It is the subject of sex, which is still a taboo subject in China.

For the 20 dancers on stage, performing The Golden Lotus was also a challenge at the beginning. They are all mainly aged between 17 to 28, and nearly all knew nothing about the book apart from the fact that it was part of the classic erotica repertoire.

For Yan Xiaoqiang, who takes the lead role of Ximen Qing, it was a different set of challenges.

"The role is all about desire, money, sex and power," he says. The Shanxi native, who has danced classical ballet since childhood, joined Wang's company in 2008 attracted by the theater's freedom.

"Frankly, I am not too curious about the book, especially the sex scenes," Yan says. "For me, the difficult thing was how to coordinate with the female dancers. We have a lot of body contact, sexual moves. Trust is important."

Wu Shanshan, who played the role of Li Ping'er, says she was worried when she read the script. "It's more challenging for female dancers. I was so nervous at the beginning."

The heavy breathing and the body contact with the male lead made her uncomfortable. Although choreographer Wang told her to relax and enjoy the dance, it took Wu six months before she could do that.

To make her dancers understand their roles better, Wang hired literature teachers to coach the dancers on their roles and tell them the stories in the background.

She also invited Oscar award-winning designer Tim Yip to create the costumes for the dance. Han Jiang, the producer and stage designer, used a palette of red, white, gold and black for each scene to reflect the emotions of each role.

"I like the last scene most, the death of Ximen Qing," says Han. "His life was full of greed and he loved women. I made the stage totally black and left a beam of light which followed him. Before he dies, he makes love to Pan Jinlian, and the whole dance ends with her solo.

"Our aim was to present a thought-provoking dance with good music, costumes and dancers. Sex is not the focus of the show," Han says.

When Wang started planning the production one and a half years ago, she was fully aware of the perception of the book as a gallery of explicit sexual chapters. In her extensive research, she found out much more about what attracted her in the first place: The social landscape of the time, which bears similarity to current society.

"It's true that a large part of The Golden Lotus has to do with sex, but it also focuses on other aspects such as lust, desire and jealousy. It's art and it connects with the audience," Wang says.

Wang's choreography in the 90-minute dance is intended to rouse the imagination of the audience and awaken its inner desires.

Jin Ping Mei was written against a background of a decaying society and Wang says that phenomenon is very similar to what is happening now.

"Maybe society today is even worse than what was depicted in the book. People these days are lured by money, and they will do anything to get what they want, without a moral bottom-line," she says.

Wang began dancing when she was nine. After winning the first of many international dance competitions in Paris in 1994, she decided to create her own body language.

She was resident choreographer for the National Ballet of China before she went on to study at the California Institute of Arts School of Dance. After her graduation in 2003, she was invited as guest choreographer at the New York City Ballet.

She became known internationally after collaborating with film director Zhang Yimou on the ballet adaptation of his film, Raise the Red Lantern. She was also one of the choreographers for the opening ceremony of the 2008 Beijing Olympic Games, directed by Zhang.

Wang is about to push the boundaries of modern dance in China further. Her company is already in rehearsal for their next year at the 2012 Arts Festival in Hong Kong, with two new works in collaboration with theater artist, Lin Zhaohua.

"I know I have been dancing on the edge, but it doesn't matter. It is definitely a lonely art in China now because modern dance is so young here. It takes time for people to understand and enjoy the art."

For Wang, it is a long, hard but happy road less traveled.